Imprints

When stories about a company’s culture, strategy, and structure are deeply rooted in the company, they become imprints. As the company develops and grows, these imprints become guiding principles that inform and justify the decisions that managers make.

“We often borrow a term from biology to emphasize the significance of these narratives that become part of the company’s DNA,” explains Peter Jaskiewicz, University of Ottawa Research Chair of Enduing Entrepreneurship at the Telfer School of Management. “These guiding principles are usually introduced by the founder and continue to guide the company beyond the founder’s tenure for years to come,” he adds.

Sticking to one’s imprints can be positive, but what if economic turmoil, a war, or a worldwide pandemic suddenly forces a company to rethink its strategy and actions and, as a result, implement major changes? In many businesses, imprints can make organizational adaptation a big challenge.

Rewriting a Company’s History

When organizational leaders need to manage a company’s guiding principles, they often reinterpret their firm’s history. One way of accomplishing this is through what researchers call rhetorical narratives. In a company, managers may re-interpret the meaning of past decisions and behaviours. “Rhetorical narratives reflect the view that the meaning of a past behaviour can change over time,” says Professor Jaskiewicz. “The meaning of something from the past is not set in stone, but constantly evolves into our narratives or stories,” he adds.

To adjust to a changing reality, organizational leaders may intentionally select a part of the past that best suits their goals and needs in the present, ignore those aspects of the past that were inconvenient or unnecessary, or even completely modify their claims about what was decided in the past.

Perhaps one of the most infamous cases in history is Volkswagen. After World War II, the German automobile giant had to reinvent itself completely in order to survive in a new political and economic reality. This included fabricating a narrative for the company, one that erased its close connection with the Nazi government. Not all companies, however, will have such a dark past to forget.

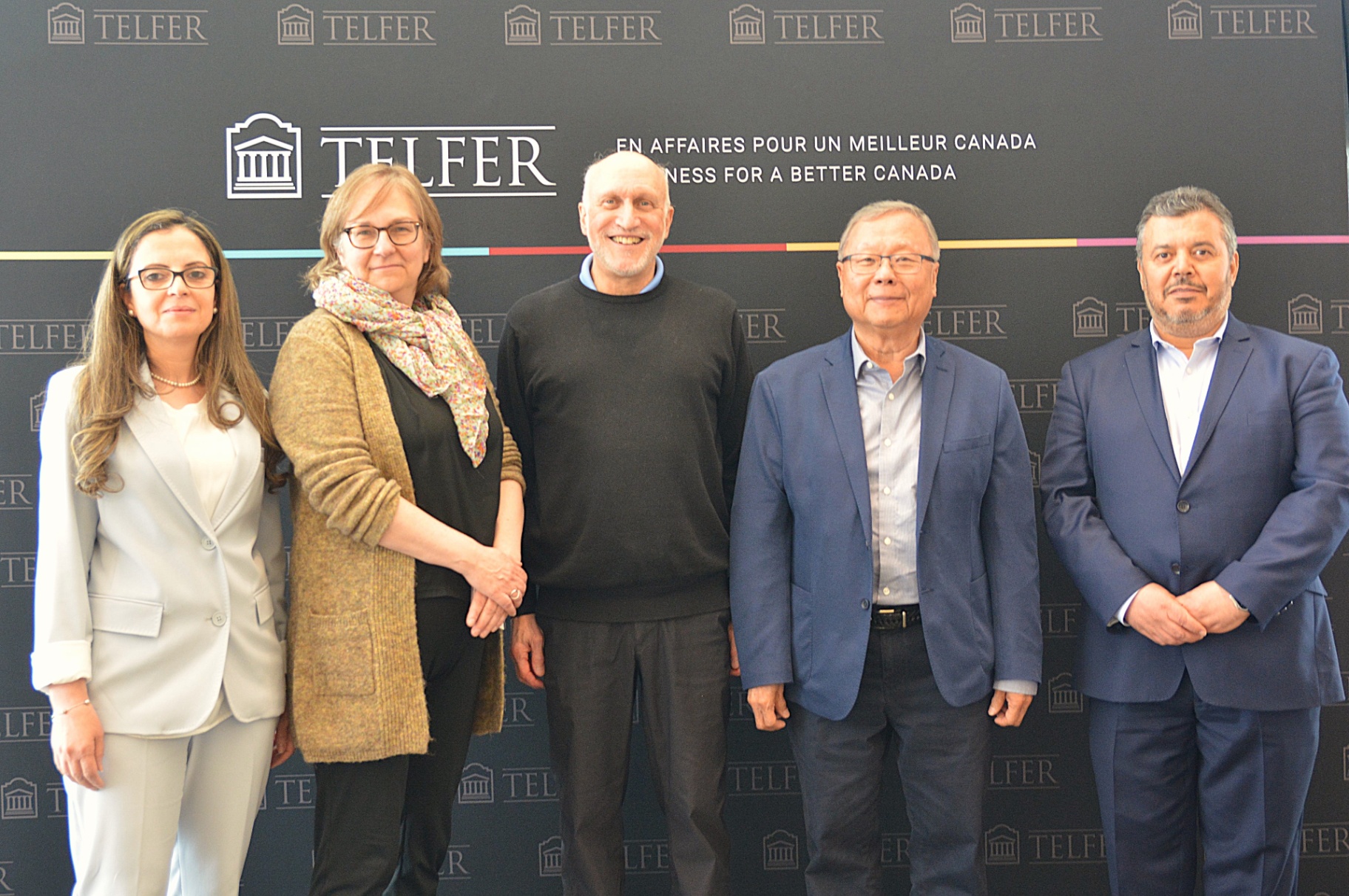

A Study of Imprints: The Gallagher Group

As businesses change and evolve, the stories that define their culture, structure, and decisions evolve, too. An important question that shouldn’t be ignored is: How do managers adapt to the changing reality without betraying the principles upon which the company was founded? This is one of the questions that motivated Paresha N. Sinha (University of Waikato, New Zealand), Peter Jaskiewicz (University of Ottawa), and other international researchers to write an article titled: “Managing History: How New Zealand’s Gallagher Group Used Rhetorical Narratives to Reprioritize and Modify Imprinted Strategic Guideposts,” published in the Strategic Management Journal.

To understand how founders and subsequent generations of managers adapt their guiding principles in times of drastic change, the authors analyzed the case of New Zealand’s Gallagher Group. Bill Gallagher Senior founded the company in 1938 in Hamilton, New Zealand, to manufacture electric fences and farm machinery. The four imprints that guided the company’s strategic decisions were: pursue engineering ingenuity, take necessary risks, engage with partners, and learn from failure. As an example, the Gallagher Group emphasized their “engage with partners” principle by looking for a partner in every new market.

A Balance between Past and Present

In the 1970s, the company benefited from rapid international expansion and technological advances, and by the 1980s, the Gallagher Group was considered a global leader in electric fencing. Then, in the mid-1980s, the company was hit hard by a global recession. Professor Jaskiewicz explains that the founder retired, and non-family managers were hired to revitalize the business:

“By analysing the company’s history, my co-authors and I found that the new managerial team implemented drastic changes to increase efficiency. This was more aligned with the environmental and competitive pressures of the time. In doing so, however, they implemented strategic changes that violated the company’s guiding principles. These decisions led to tensions with employees, the owning family, and firm stakeholders.”

In the late 1990s, the leading non-family managers left, and the founder’s son became the new CEO. By then, the company had survived the crisis and was ready to embrace its sidelined principles, which had made it successful before. Familiar with the company’s imprints, the family CEO selectively prioritized some of these principles and modified others to ensure that what the company had stood for could also match client expectations at the time. The company has experienced strong growth in new fields since then. Today, the Gallagher Group is a global leader in airport security systems.

Implications for Businesses Today

Jaskiewicz explains that changing organizational principles can be difficult for businesses, especially to those that face unprecedented challenges and need to act rapidly:

“Sometimes it can take a pandemic to force businesses to adjust to a very different reality, whether that means they need to adapt their decision-making strategies, culture, or structure to survive in a more digital and socially distanced world. During these times, organizational leaders should keep in mind that their guiding principles have been valuable but may not always align with the new reality. This requires them to make important choices, including revising their past principles for an impact in the future.”

Professor Jaskiewicz is a Full Professor and University Research Chair in Enduring Entrepreneurship at the Telfer School of Management. His research focuses on entrepreneurship and family business. Learn more about his work.

-zhang.png)