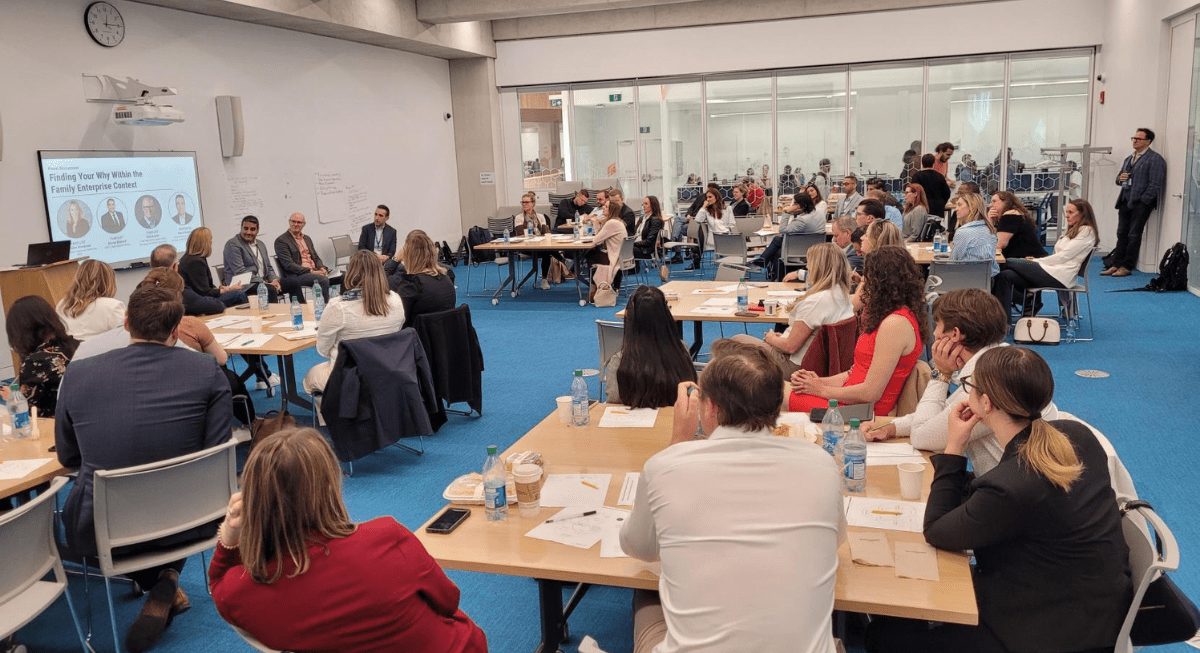

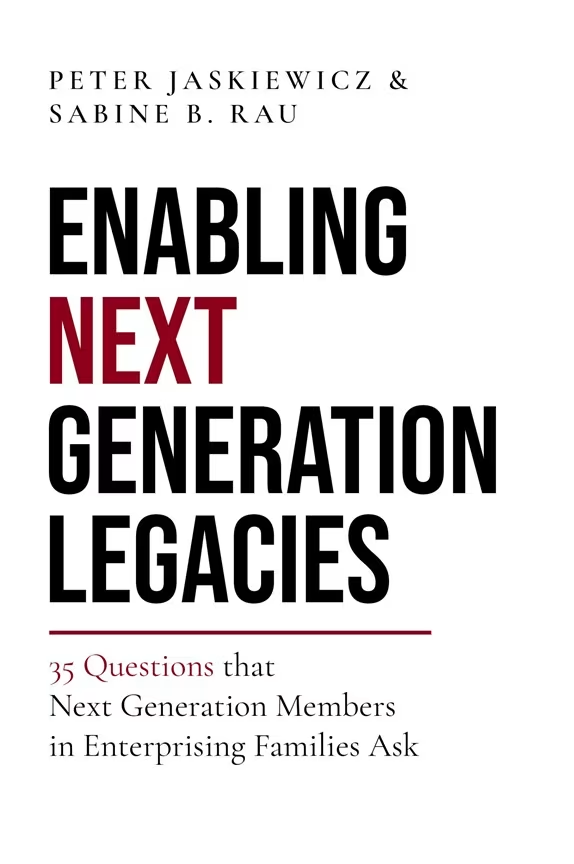

The Family Enterprise Legacy Institute has been featuring select parts from the book, Enabling Next Generation Legacies: 35 Questions That Next Generation Members in Enterprising Families Ask. The result of years of international research and practical experience, Enabling Next Generation Legacies delves into the unique challenges that confront family enterprises. Telfer professors Peter Jaskiewicz and Sabine Rau have brought together the world’s leading academics, practitioners, and enterprising families to answer the most pressing questions faced by Next Generation members in a short and concise, yet meaningful way.

The book consists of best practices, real-life examples, and additional critical questions for reflection from nearly 100 contributors from 27 different countries. Expert commentaries come from members of the world’s leading family businesses including Auchan (France), Saputo (Canada), and Sabra (Israel), as well as from various academic experts from business schools around the globe like Kellogg, IMD, and INSEAD.

Below, read an expert response to a pressing question raised by Next Generation members.

My Parents Do Not Talk About Their Retirement. How Can I Start the “What’s Next After You Retire from the Business” Conversation with My Parents?

Response by Ivan Lansberg, U.S.

The quick answer is to approach the retirement conversation with empathy and smarts. Empathy is needed because if Next Gens can’t grasp why it is so difficult to let go of a business their parents have created and/or lead successfully, Next Gens will not be able to engage with their parents constructively. Next Gens also need smarts, because to facilitate the conversation in a way that is pragmatic and focused on the needs of all stakeholders requires the kind of long-term multistep strategy needed in games like chess. Succession should never be an event; it should always be a process. So rather than one conversation, plan for a multi-year process of conversations—carefully planned so that Next Gens start with the easier, though substantive issues, and work their way up toward the most difficult ones.

The empathy element often poses the biggest challenge because there is a built-in generational asymmetry when it comes to succession. While parents were once young and can draw from that experience to understand the challenges their children face in establishing their own credibility as aspiring leaders, Next Gens have never been old, so for them to imagine the vulnerabilities their parents might feel when contemplating retirement, and shedding lifelong engagement with a business they built, will always require a more significant emotional and cognitive stretch.

So, while Next Gens ought not to be afraid of these conversations, they do need to respect the challenge the transition poses and learn to appreciate that retiring senior leaders require a system-wide approach to facilitate a process of change. This is where patience, strategy, and smarts matter.

Step 1: Establishing Credibility

The first step is to ensure that Next Gens have done all they can to establish their own credibility as viable successor candidates. As Machiavelli once remarked, “power is never given, it is always taken,” an idea suggesting that the most effective successions are always driven by the aspirations and actions of succeeding generations. But how Next Gens acquire power in a family enterprise makes all the difference. For the burden does fall on them to provide evidence to their parents—and, indeed, to all the shareholders, employees, customers, and suppliers as well as to the communities where the business operates—that they will be in good hands under their leadership. The more that Next Gens have invested in their own personal and professional development, and the more they have demonstrated their competence to lead and add value, the easier the retirement conversations will be. This will also help to evoke in their parents both confidence and pride in Next Gens’ accomplishments, and merit and pave the way to mutually respectful conversations.

Step 2: Risk Management

Succession planning is always an exercise in risk management. Ensuring that the team taking charge has the competencies that the system needs is essential. It is also critical to ensure that the outgoing seniors financial security is protected no matter what. As I often tell clients, “if you get out of the cockpit, get off the plane.” The new leadership has to assume the risk for the strategic, financial, and organizational decisions they make. Otherwise, they will never earn the authority needed to lead.

Understanding the challenge that retirement poses for parents requires getting your head around the fact that succession calls for them to enable a transition to a future that doesn’t have them in it. Like Moses, they must gather the foresight and generosity to lead a people to a promised land that they cannot enter. And this requires them to have the courage to face the loss of their roles, often a critical part of their stature and identities. Ultimately the transition also calls for them to come to terms with their own aging, obsolescence, and mortality. No matter how caring and empathic Next Gens are, helping their parents mourn the losses that come with succession is imperative because it’s so hard for parents to do so on their own. Perhaps the most useful thing that can be done is ensuring that there are people in the system who have deep experience with these transitions and can advocate for having a succession plan in place, and who also have the trust and respect of the senior leaders. For example, often the most important allies that families can have for this process are the independent directors on their board. Building a strong relationship with them is a key priority for the Next Gens. If the business doesn’t have a strong board, then putting one in place should be a key priority. Families should make sure that at least one of their directors is a retired business owner who has done a great job of planning their own retirement and can speak with the authority and credibility of someone with personal experience.

Step 3: Readiness

The most basic measure of succession readiness is gauging the degree to which fundamental decisions are still made by the parents. A good question for Next Gens to ask themselves is if they lost both parents today were would they be missed the most? What would happen to the ownership? What would happen to the operational side of the business? And, of course, what would happen in the family itself? Attending to the answers to these questions helps Next Gens (and hopefully the board) sketch the work still to be done.

The ebb and flow of succession in any system is driven by the biological clock. The first responsibilities that typically transfer are managerial and operational roles; the second are nonvoting shares (typically driven by estate planning prerogatives) and next comes control over the voting shares. Typically, it is the family leadership roles that are the last to be handed down. This is because the hierarchies of the family are the most enduring. As a client once told me, “the definition of a kid is someone with living parents.”

You know that family leadership has been passed down when family gatherings, holidays, and rituals are no longer held in the parents’ home but in the homes of Next Gens. Understanding this natural progression can provide a useful high-level GPS to navigate the transition and frame productive conversations.

Motivating parents to imagine what life would look like after the transition is also critical. Succession requires both a destination and a path. It is much easier to be pulled into roles (and into a life) that parents want than to be pushed out of roles they know well and are deeply attached to. Eliminating some of the ambiguity about the future and ensuring that some level of rigor has been built into the definition of the parents’ roles matters. In this regard, it is critical for them to see that there are, in fact, ample opportunities available for parents to continue living engaged, purposeful, and fulfilling lives. Leaders are often ignorant about the ways in which their skills and capabilities are re-deployable in new arenas like board service, philanthropy, community engagement, politics, or even a new venture.

Also, Next Gens should bear in mind that the enemy of succession is surprise. From the moment the owners, board, and senior management start thinking about succession to the moment when the plan is fully implemented, can take as long as five-to-ten years. It is imperative to couple succession planning with a contingency plan that delineates what the family would do in the event of an unexpected occurrence. Several times in my career, I’ve had to help clients deal with the untimely death of the successor on whose shoulders the succession plan rested. In sum, the process calls less for Next Gens to have the retirement conversation directly and more for them to ensure that there is a the right set of conditions in place so conversations can be had between their parents and the people they are most likely to listen to on this issue.

Ivan Lansberg is a senior partner at Lansberg Gersick and Associates (https://lgassoc.com). He was one of the founders of the Family Firm Institute and the first editor of its professional journal, the Family Business Review. After receiving his BA, MA and PhD from Columbia University, Ivan taught at the Columbia Graduate School of Business. He became a professor of organizational behavior at the Yale School of Organization and Management for seven years before going into consulting. His books Succeeding Generations and Generation to Generation, published by Harvard Business School Press, have been widely praised as landmark works. Ivan is on the faculty of Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University.

Commentary by Paloma Rivadulla Durán, Spain

My family company Fernando Durán S.A. is the first auction house in Spain. It was created in 1969 and continues to be one of the best companies in its sector at a national and international level. We act as intermediaries; that is, we put buyers and sellers from all over the world of art and luxury objects in contact with each other using our rooms as the main venue to exhibit the objects and establish direct contact with our clients. As the objects or paintings become the property of other collectors, professionals, or private individuals on the day of the auction, it will be the experts who will stipulate a minimum estimated price, but it will be the market that will set the final price.

My role within the company is varied. Mainly, I am in charge of collecting works of art, jewelry, and watches with my mother, Paloma Durán, director of the company. We travel all over Spain valuing objects and offering our services of appraisal, transport, auction sales, and storage. Since I am the youngest person of the hired staff and since I am fluent in the world of technology, internet, and social networks, I am also in charge of updating the hardware and software of the company, installing new computer equipment, designing the website, and leading a team of programmers.

As for my mother's retirement, I have learned that it is a delicate matter for both the company and for her. A family member who has dedicated her life to running such a company should never retire.

Let me explain. My mother's bond with the company is not only a professional attachment based on legal ownership, but also an identity bond. For this reason, I would speak of a presidency and not of a retirement, because we are dealing with a special company.

It may seem paradoxical to speak of a retirement in these terms—thinking of the creation of a new position. Retirement is undoubtedly an important right, but a person like my mother will make use of this right without disappearing from the company. To make this possible, we need to create an appropriate context for her case and others like hers. It is in this sense that I speak of presidency. People like my mother deserve to always be a part of their company, because it is a question of personal identity.

The company is part of my mother’s (and other family members’) identity and leaving it would be like not being herself anymore. Therefore, for those who love to work within the family business, it would be necessary to create a new status within it or to create a connection that makes them part of it until they decide otherwise or until that participation becomes impossible.

For many, especially for those who find themselves in a similar situation to my mother's, a retirement that is understood as disappearance from the company creates an inner rupture—a vital tearing apart. Even more, when new generations of the family take over the company, leading the project in a different way, the change of direction and style is a threat not only to my mother, but also to the family business. This is why conflicts and delays in making decisions in favor of the company's growth arise around change. Indeed, the retirement of people like my mother must be understood in terms of a change rather than a disappearance: a change from being in management to being the chairman of the board. By changing the context in this way, the bond between my mother and the company takes on a deeper meaning; there is no rupture because there is no disengagement. I know that my mother would have wanted to devote herself to other tasks within the company instead of taking on management for so many years. I also believe that there are others who have experienced the same. Therefore, it would be interesting to consider the possibility of enjoying retirement without having to give up the family business. My mother's retirement will not mean a fall into passivity, but rather new activity: the creation of a new department within the company. It seems hard to believe or even ironic, but we will do it this way. Moreover, I am confident that this will not add to the company's burden or hinder its development. Quite the contrary, it is about creating a community that does not discard anyone before their time. We are more humane this way.

In my opinion, to be able to venture into this type of conversation, the first thing to do is to work hard and assert yourself inside and outside the company, spend time thinking about that relative who will have to retire, and listen to him or her. The three steps—work, think, and listen—help you to realize what that family member wants in relation to the company. That's how I discovered it.

Enabling Next Generation Legacies: 35 Questions That Next Generation Members in Enterprising Families Ask is now available in eBook and hardcopy. All royalties from Enabling Next Generation Legacies go towards the University of Ottawa’s Telfer Fund, helping students in need.

To read more about how Telfer is shaping the conversation about the future of family enterprise, visit the Family Enterprise Legacy Institute and subscribe to our newsletter to stay up to date.