A new Telfer study shows that gender preference influences how entrepreneurial families prepare the next generation and support their business education and careers.

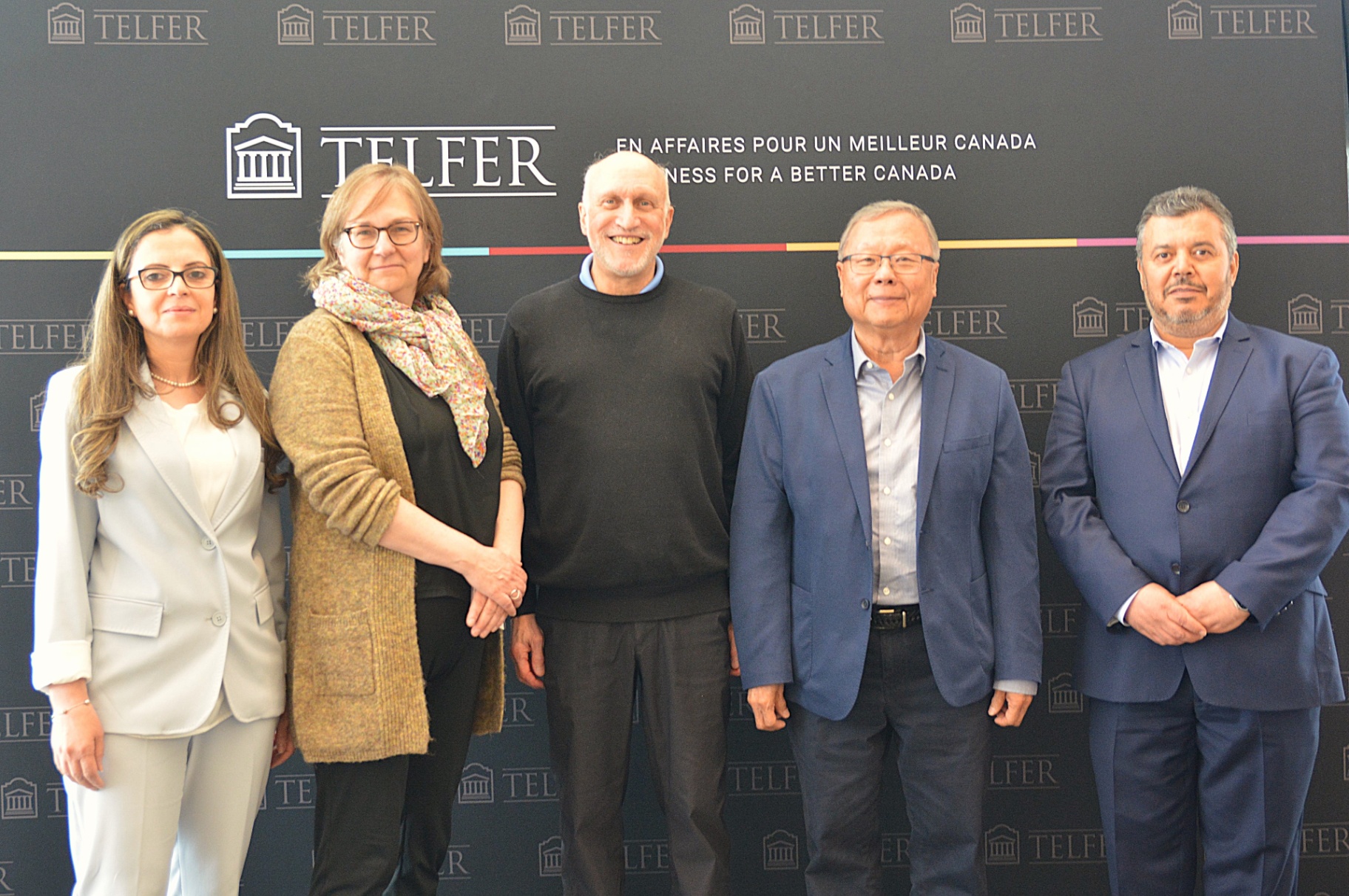

When nurturing the next generation, entrepreneurial families often prepare their children differently for careers, based on gender. Now, Telfer professors Peter Jaskiewicz, James Combs and Sabine Rau have shown how this gender bias affects the succession strategy in multi-generational family firms.

Gender bias influences how some families raise sons and daughters and whether they get involved in the family firm. But it also has long-lasting consequences even for children who don’t get involved in the family firm or who choose to pursue their entrepreneurial passion elsewhere.

Little support for daughters

In conversations with 24 adult children raised by entrepreneurial families, the researchers found that:

Seven of the nine sons (78%) pursued careers in entrepreneurship.

Only one of the 15 daughters (7%) received an entrepreneurial education and became an entrepreneur.

Daughters were not encouraged to pursue an education in entrepreneurship, gain business experience or start new ventures.

Families offered financial support or seed funding to sons who wished to start a new business, but not to daughters.

Sons were often brought up to be entrepreneurial, whether this meant taking over the firm, assuming a leadership role in another firm or starting their own venture. But daughters received little or no incentive to develop their own leadership skills and foster their entrepreneurial spirit.

The team also found some surprises:

Even some of the less traditional families studied didn’t offer financial support for daughters to pursue entrepreneurship, although the daughters had business education and relevant experience.

Daughters were only supported in entering the family firm’s leadership or starting their own businesses when there was no son.

Old traditions die hard

The researchers wondered why daughters hit the family firm glass ceiling, even in families with an entrepreneurial legacy. They noted that many of the multi-generational businesses studied were founded centuries ago. With the exclusion of women from power normalized in institutions like religion, law and the family, Jaskiewicz believes that “these practices became so deeply embedded into cognition that some families stopped questioning them.”

First-hand examples of gender bias

Emma O’Dwyer, regional manager at Family Enterprise Canada and Susan St. Amand, founder, CEO and president of Sirius Group Inc. and Sirius Financial Services, grew up in families that owned firms. O’Dwyer recognizes how hard it can be for the next generation to identify or challenge traditions. “Gender bias can be present in family interactions every day, but as a child you just do not know any different to what you are experiencing,” she says.

Thinking of her family, St. Amand says that “Daughters were meant to find husbands, marry and stay home to raise children and grandchildren.” As for O’Dwyer’s family, the boys were far more encouraged to develop their professional skills at a very early age. “Once they were 14, they went to work in the family business for long days throughout the summer, no questions asked.”

Long-lasting impact on women

For Jaskiewicz, “Families need to understand that gender bias favours men while discouraging women from building their legacies in the family business or pursuing entrepreneurial experiences elsewhere,” he explains. In doing so, these families limit women’s contribution to business.

He also believes that gender bias also has long-lasting consequences. “Even when these female non-successors have opportunities to acquire relevant knowledge and work to start a business, becoming entrepreneurial can still be an uphill battle,” he says.

Many women don’t pursue entrepreneurship outside of the family because of the reduced emotional and financial support from the family. Jaskiewicz adds:

“Sometimes (families) following traditions can be very costly, effectively cutting off 50% of the next generation.”

Read the study

James G. Combs, Peter Jaskiewicz, Sabine B. Rau, and Ridhima Agrawal. “Inheriting the legacy but not the business: When and where do family non-successors become entrepreneurial?” Journal of Small Business Management.

To find out more about the Family Enterprise Legacy Institute at the Telfer School of Management, visit our website.

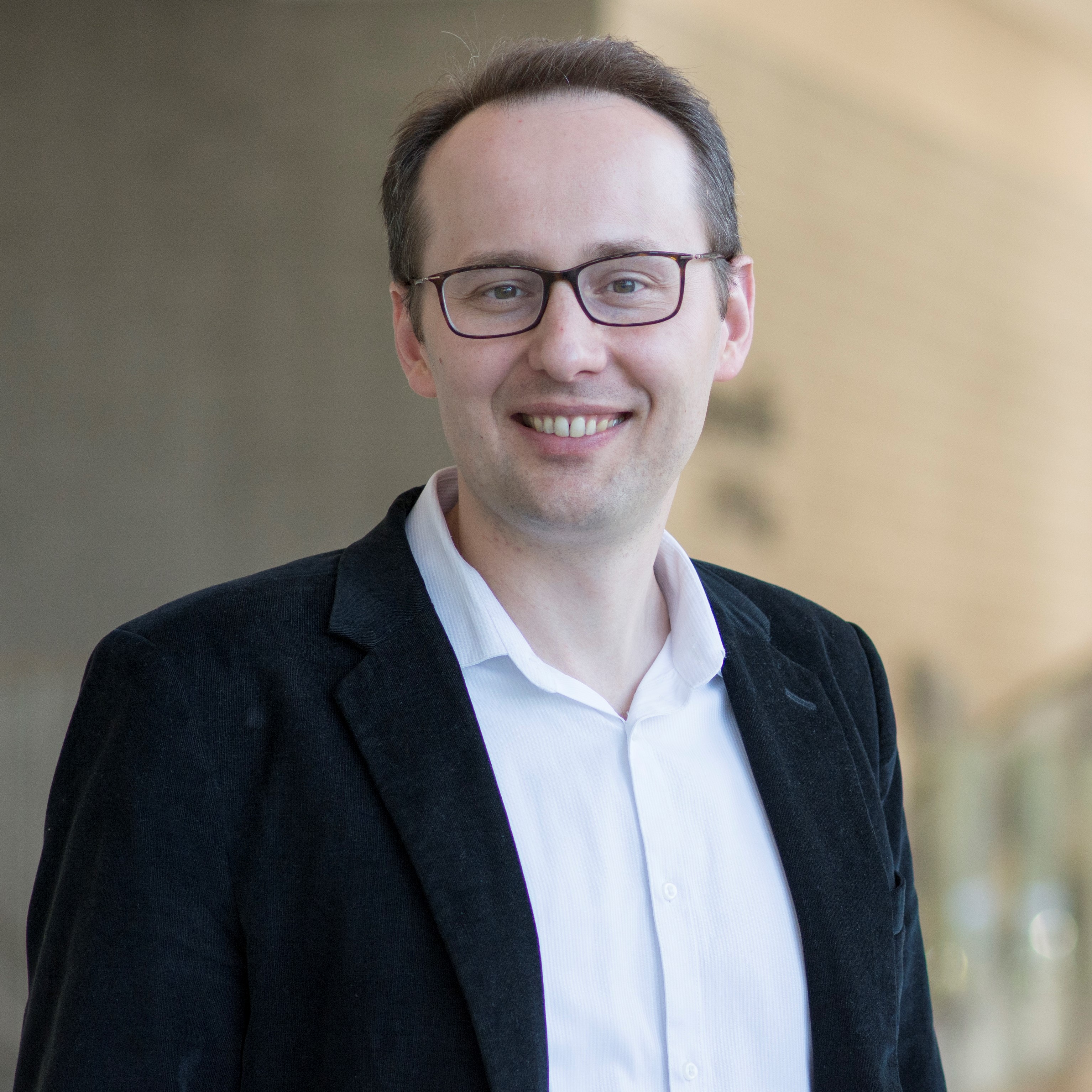

Professor Jaskiewicz is a Full Professor and University Research Chair in Enduring Entrepreneurship at the Telfer School of Management. His research focuses on entrepreneurship and family business. Learn more about his work.

Sabine Rau is a Visiting Professor at the Telfer School of Management and at ESMT, Berlin. She is also is Partner at Peter May Family Business Consulting. Her research focuses on the intersection of family and family business.

James Combs is a Visiting Professor at the Telfer School of Management and a Full Professor at the Univeristy of Central Florida. His research interests include franchising, the role of family dynamics in family firms, and the factors that foster entrepreneurship in family firms. Learn more about his research.