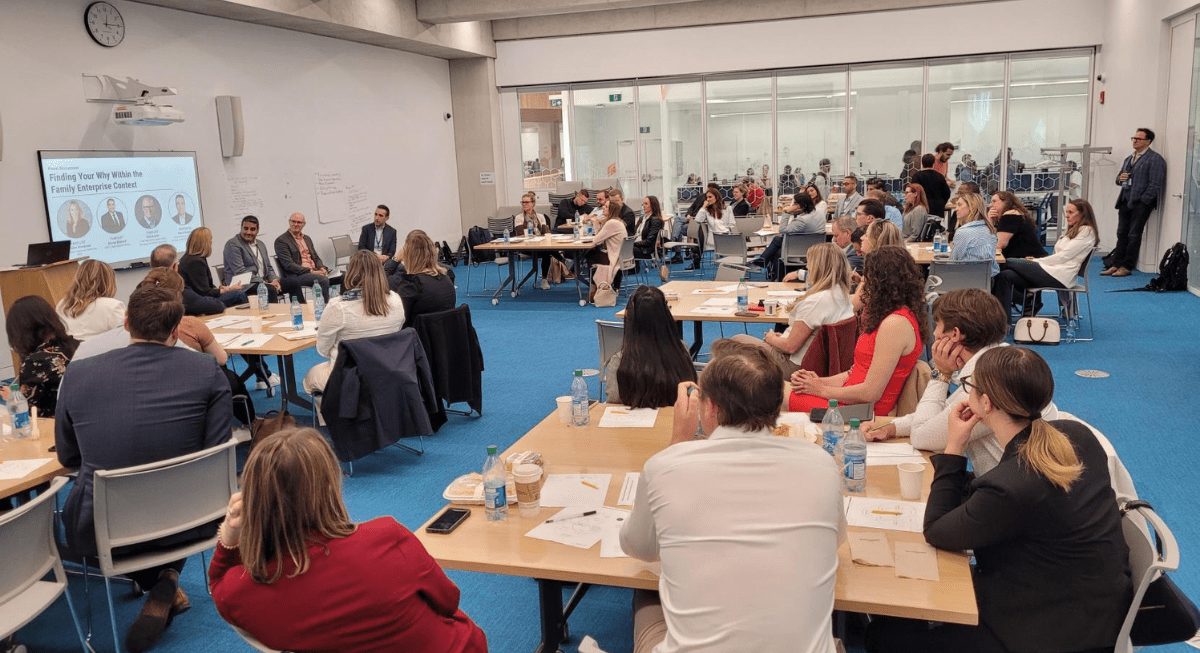

Au cours des prochains mois, le Carrefour du savoir Telfer publiera des extraits du livre intitulé Enabling Next Generation Legacies: 35 Questions That Next Generation Members in Enterprising Families Ask.

Résultat de nombreuses années de recherche et d’expérience pratique à l’échelle internationale, cet ouvrage s’intéresse aux défis particuliers auxquels font face les entreprises familiales.

Peter Jaskiewicz et Sabine Rau, respectivement directeur et collaboratrice à l’Institut de l’héritage des entreprises familiales (FELI) et membres du corps professoral de l’École de gestion Telfer, ont réuni des universitaires, des familles entrepreneuriales ainsi que des praticiennes et praticiens mondialement reconnus afin de répondre, de manière brève, concise et néanmoins pertinente, aux questions les plus pressantes auxquelles est confrontée la prochaine génération.

Fort de l’apport de quelque cent collaboratrices et collaborateurs issus de 27 pays, le livre présente les pratiques exemplaires, des exemples concrets ainsi que des questions essentielles visant à susciter la réflexion. Les commentaires d’experts proviennent de membres des entreprises familiales les plus importantes du monde, dont Auchan (France), Saputo (Canada), and Sabra (Israël), ainsi que de divers spécialistes universitaires travaillant dans des écoles de gestion renommées telles que Kellogg, IMD, et INSEAD.

Vous trouverez ci-dessous la réponse à une question pressante qui se pose aux entreprises familiales (dans sa version originale anglaise).

Do I Deserve the Business and/or Wealth I Will Inherit?

Response by Nava Michael-Tsabari, Israel

Like Hamlet's contemplation reflecting his own self-doubt ("to be or not to be"), this is the question most Next Gens of a family firm ask themselves. Wealth is defined as the total assets owned by a family at one time[i], yet family firms have emotional value as well.[ii] Even medium-sized family firms (businesses that generate about $13 million in revenues with some thirty employees) may create wealth which categorizes them among the wealthiest class in society[iii]. However, Next Gens have mixed feelings about succession of firm and wealth, and when asked about it, their feelings of obligation are twice as high as their own desire to inherit.[iv] I am a third-generation member of a multi-billion-dollar family firm, as well as an academic. H ere is my answer taking into account my life experience. Scholars describe different attitudes that Next Gens have toward the family firm, however, these mainly refer to pursuing "a career in their family business,"[v] and not to the dilemma stated above. Scholars refer to employment in the firm, and not to the question of entitlement of the business and/or the wealth.

I Was Not the "Chosen One"

Growing up, it was already decided for me that I did not deserve the firm. As in any family, individuals are shaped by their unique perspective. So am I, the eldest child of our third generation. My cousin was the chosen one, expected to inherit the leading position being the daughter of the eldest son, while I was born to the younger sister. My uncle preferred his own daughter. He decided that I was not worthy of the firm, which was even more difficult to deal with because nothing was explicitly explained. Trying to figure out who I w as in these circumstances was complicated, exacerbated by the question of whether I still deserved the wealth. The family wealth felt like a mixture of burdens, responsibilities, and callings from my ancestors, need to justify myself and a constant reason to worry. I was afraid of failure being measured up to past successes, which were created by others. I was worried I’d let everyone down. I have not yet read a study that describes a similar mixture of feelings—just a few anecdotes. Like, for example, Phil Knight, the founder and owner of Nike, describing how he had to fight wealth's trial "to define" him. In his initial search he bought a Porsche and wore sunglasses everywhere.[vi] The good news is that finding purpose and meaning in later years helped me also enjoy and feel at ease with wealth. The bad news is, it is a long process that demands personal growth.

It is a Long Journey

My late grandparents, who I loved and adored, had expectations. I felt the weight of tradition. I was born into the family firm and did not have an identity that was separate from it. Being a Next Gen is a huge part of how I define myself. This is probably true for most Next Gens. How can I feel that I deserve anything when I do not know who I am? Finding the balance between being the next link in a chain to being an independent particle is the result of a long journey, which began early for me. Being born to the family that is connected by shared mission, history, and identity, what they think and expect has an enormous influence. A Next Gen receives implicit and explicit messages regarding how they should feel, think, and behave, like "don't come to the business." It should be no surprise that many Next Gens who feel that they want to control their own lives have been found to prefer not working for the family firm.[vii] My trajectory was first defined by family members from the outside. It took ye ars to regain my control and define my identity from the inside. Finding the balance between listening to my inner voice and outside voices is the result of this long journey.

Interestingly, the mistakes I made along the way, the actual and psychological losses that I endured as I was stumbling while trying to find my path—all these felt like the cost I had to pay. I was rebellious, lost money, and did not speak with my mother for a year. It was as if the mistakes alleviated the weight of wealth and allowed for a more relaxed attitude towards it. I kind of "paid for it" myself, didn't I? Finding the balance between the price one pays and the rewards one earns helps finding a justification for one’s own path and identity.

Looking Back—the Lessons I Learned

Looking back, finding my path has worked in mysterious ways. The less I searched for solutions outside, and the more I learned to give meaning to what I did, the more I felt peace of m ind. Finding my own purpose, which resulted in transforming the beautiful phenomenon of the family firm into research and teaching to other scholars and members of family firms, helped me resolve the entitlement issues. Turns out that when one co-creates her own path, it gives a feeling of competence and increases a sense of self.[viii] The feedback from listeners who tell me my insights heal them, fills up my heart. Knowing who I am made it possible to define what I deserve.

My three lessons were (1) finding out who I was as an individual, (2) not being afraid to make mistakes, and (3) learning what defines meaningful work for me.

After a long journey I realized that I am part of the family firm and its wealth, and it is part of me, regardless of what others think. I experienced the "paradox of choice,"[ix] where having more opportunities actually led to confusion and dissatisfaction. I had to learn that the family firm is not the only thing that defines me. I am confident and happy with the heritage and the lessons I can share with others. It is the result of a search for how I could give meaning to my actual and emotional inheritance. There will always be outside voices ridiculing or criticizing; however, it is the answers one finds inside that pave the way to the balance. It requires time to mature, but the possibilities to leverage wealth into contributions to others is an outcome worthy living for.

Nava Michael-Tsabari, PhD, is the founder and director of the Raya Strauss Center for Family Firm Research at the Coller School of Management, Tel Aviv University. Her dissertation from the Technion—Israel Institute of Technology was the first one on family firms in Israel. Her research examines emotions, organizational culture, and employment in family firms. She is a third-generation member of the Strauss family firm, a publicly traded multinational food conglomerate.

4.2 Do I Deserve the Business and/or Wealth I Will Inherit?

[i] Lisa A. Keister, “The One Percent,” Annual Review of Sociology 40, no.1 (January 2014): 347-367.

[ii] Thomas M. Zellweger and Joseph H. Astrachan, “One the Emotional Value of Owning a Firm,” Family Business Review 21, no.4 (December 2008): 347-363.

[iii] Michael Carney and Robert S. Nason, “Family Business and the 1%,” Business & Society 57, no.6 (July 2018): 1191-1215.

[iv]Bill Noye, Dominic Pelligana, Michelle De Lucia and Greg Griffith, “Family business—the balance for success: Colliding generational perspectives, reinvigorating successful family businesses,” The 2018 KPMG Enterprise and Family Business Australia survey report (Australia: KPMG Enterpr ise, 2018).

[v]Pramodita Sharma and Irving P. Gregory, “Four Bases of Family Business Successor Commitment: Antecedents and Consequences,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 29, no.1 (January 2005): 13-33.

[vi] Phil Knight, Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of Nike (New York: Scribner, 2016), 1-400.

[vii]Thomas Zellweger, Philipp Sieger and Frank Halter, “Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background,” Journal of Business Venturing 26, no.5 (September 2011): 521-536.

[viii]Daniel Mochon, Michael I. Norton and Dan Ariely, “Bolstering and restoring feelings of competence via the IKEA effect,” International Journal of Research in Marketing 29, no.4 (2012): 363-369.

[ix]Barry Schwartz and Andrew Ward, “Doing Better but Feeling Worse: The Paradox of Choice,” in Positive Psychology in Practice, eds. Alex Linley and Stephen Joseph (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2004), 86-104.

L’ouvrage intitulé Next Generation Legacies est maintenant disponible en copie numérique et physique. Toutes les redevances de Enabling Next Generation Legacies sont versées au Fonds Telfer de l'Université d'Ottawa, qui aide les étudiants dans le besoin.Visitez le site www.35questions.com pour plus de détails.

Pour en savoir davantage sur la façon dont Telfer alimente la discussion sur l’avenir de l’entrepreneuriat familial, visitez le site de l’Institut de l’héritage des entreprises familiales et abonnez-vous au bulletin d’information.