The Role of Leadership in Building More Sustainable Cities

By Lidiane Cunha

The construction and development industry is a large contributor to the Canadian economy, employing over 1 million people and accounting for 6% of national GDP. Unfortunately, it is also one of the worst environmental offenders, consuming over 50% of all raw materials extracted, producing 30% of solid waste disposal, and contributing approximately 40% of global CO2 emissions. Despite the growing and urgent need for more socially and environmentally sustainable urban developments, the construction and development sector has been one of the slowest industries to adapt to more sustainable practices.

How can this industry build more urban neighborhoods that respect the environment and contribute to the social and economic development of local communities? The answer might lie in the hard work of leadership. A recent study co-authored by Associate Professor Daina Mazutis suggests that leadership plays a major role in driving forth sustainable urban transformations. In the article published in the Journal of Cleaner Production, the authors analyzed the case of the Zibi Development. The development is a One Planet Living community currently under construction in Canada’s capital region. We interviewed Professor Mazutis to find out about the role of leadership in bringing radical change to the sector.

What are the main barriers impeding construction companies from achieving more sustainable outcomes in the construction sector?

The construction and development industry, like many others, is characterized by competitive dynamics that create small margins and therefore extreme cost pressures. Unfortunately, there is a misconception that sustainability is expensive, when in fact, more sustainable designs result in much lower building operating costs over time.

Tell us why you chose to analyze the Zibi Development in your study.

When we moved back to Ottawa in 2015, I was introduced to Jonathan Westeinde, Founder and CEO of Windmill Development Group through a mutual friend, and he agreed to guest lecture in class on Business in Society, where he told the Zibi story. Given that I research leadership and sustainability, I was hooked! Here was someone trying to build one of the world’s most sustainable communities right in our backyard! We kept in touch and the following year and the next, I took some of my students to tour the Zibi site with Jonathan. This experience led us to write a case, which has been taught in some of my classes. Ever since, I have been following their progress with great interest and so we decided to dive deeper and examine the work of the leadership team responsible for the Zibi project. We wanted to bring wider attention to what they were doing.

What were the main challenges faced by the leadership team at Windmill Developments in the Zibi Development? How did they address these challenges?

As a research site, the Zibi development is particularly interesting due the enormity of the challenges Windmill development faced, beginning with acquiring the right to develop the property through to implementing their vision. The land in question is an abandoned industrial wasteland that lies partially in Quebec, partially in Ontario and has portions monitored by the National Capital Commission (a federal agency). The land is also considered unceded Algoniquin territory. The political and cultural minefield is unparalleled and yet Windmill was successful in navigating this complexity, securing broad based buy-in for their One Planet Living design. They are currently in the thick of construction.

Your study focuses on how sustainability leaders play a pivotal role in promoting change in the construction sector. Can you identify the 5 critical tasks leaders need to take on to instill sustainable innovation in the sector and deliver more sustainable urban developments?

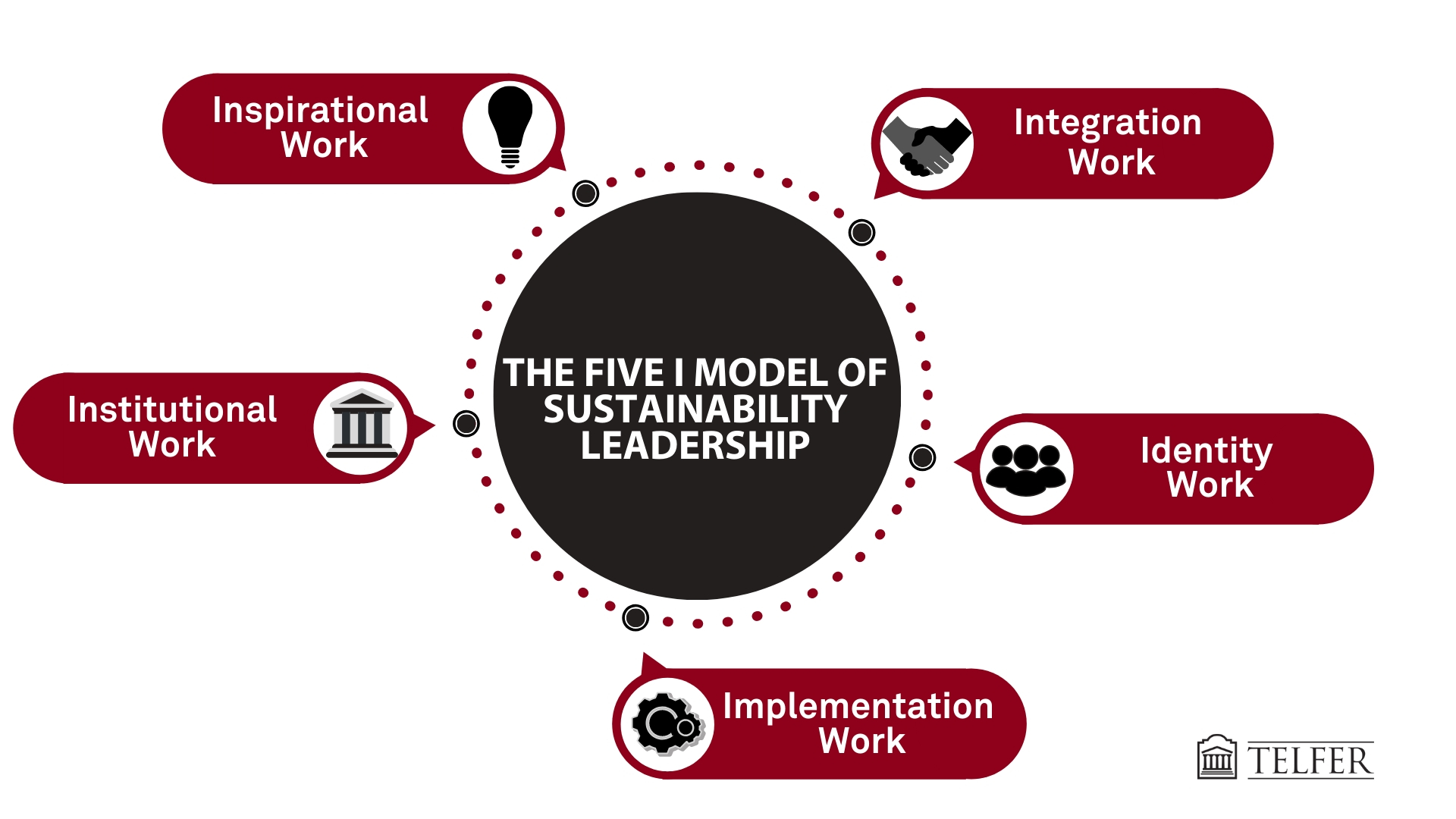

Here is what we found that sustainability leaders do drive more sustainable urban transformations. We call it the 5I Model of Sustainability Leadership:

- Inspirational Work: Sustainability leaders are able to rethink traditional approaches to construction and development by learning from international best practices and partnering with outside experts to create a compelling vision for the community.

- Integration Work: In order to negotiate complex multi-partner agreements, sustainability leaders engage stakeholders in a collaborative decision-making process and look for general principles that everyone can agree on.

- Identity Work: The most difficult task for sustainability leaders is to manage dissenting perspectives so all involved can retain their individual identities while building a new collective identity. This requires open, transparent and frequent communications and partnering to develop inclusive joint projects.

- Implementation Work: This is the nuts and bolts of designing and building a sustainable community. Sustainability leaders can implement the bold objectives set by hiring the right people with the right skills and without compromising on the original principles.

- Institutional Work: Sustainability leaders work hard to maintain commitment to the vision by embedding sustainability into every aspect of the project and re-confirming alignment at regular intervals. If they fail to do so, the competitive pressures in the industry can easily derail more sustainable outcomes.

What’s the takeaway of your study for sustainability leaders in the sector?

Designing and developing sustainable communities may be difficult, but ultimately, the rewards far outweigh the challenges. The Zibi Development has won many international awards that have led to more contracts and more sustainable construction and development projects. Positive changes are possible, even in the most traditional industrial sectors!

Daina Mazutis is an Associate Professor of Strategy at the University of Ottawa where she also holds the Endowed Professorship in Ethics, Responsibility and Sustainability. Her research focuses on leadership, strategy and sustainability. Learn more about her work.

.jpg)